English learning - writing

Reading

Evaluation during Reading

After you have asked yourself some questions about the source and determined that it’s worth your time to find and read that source, you can evaluate the material in the source as you read through it.

Read the Preface

- What does the author want to accomplish?

- Browse through the table of contents and the index. This will give you an overview of the source.

- Is your topic covered in enough depth to be helpful?

- If you don’t find your topic discussed, try searching for some synonyms in the index.

Who Is the Author?

- Is this person reputable?

- If the document is anonymous, what do you know about the organization?

Check for References

- Check for a list of references or other citations that look as if they will lead you to related material that would be good sources.

Determine the Intended Audience

- Are you the intended audience?

- Consider the tone, style, level of information, and assumptions the author makes about the reader. Are they appropriate for your needs?

Fact, Opinion, or Propaganda?

- Try to determine if the content of the source is fact, opinion, or propaganda.

- If you think the source is offering facts, are the sources for those facts clearly indicated?

- If the source is opinion, does the author offer sound reasons for adopting that stance?

- Are arguments very one-sided with no acknowledgement of other viewpoints?

Check for Evidence

- Do you think there’s enough evidence offered?

- Does the author use a good mix of primary and secondary sources for information?

- Is the coverage comprehensive?

- As you learn more and more about your topic, you will notice that this gets easier as you become more of an expert.

Determine the Tone of the Writing

- Is the language objective or emotional?

Look for Generalizations

- Are there broad generalizations that overstate or oversimplify the matter?

- Are there vague or sweeping generalizations that aren’t backed up with evidence?

Is the Source Current?

- How timely is the source? Is the source twenty years out of date?

- Some information becomes dated when new research is available, but other older sources of information can be quite sound fifty or a hundred years later.

- The previous information is derived from the Purdue Online Writing Lab’s website (owl.purdue.edu/owl/research_and_citation/conducting_research/evaluating_sources_of_information/evaluation_during_reading.html)

Research

Before Reading a Research Source

- Ask yourself these questions as you read the introduction, conclusion, author’s notes, biographical notes and any other inclusions that the publisher might make, as appropriate to your source.

What type of research source is this?

- Can you document (cite) where the research source came from?

During Reading a Research Source

- Look for answers to these questions while you are reading and incorporate some of the answers to these questions into your research notes.

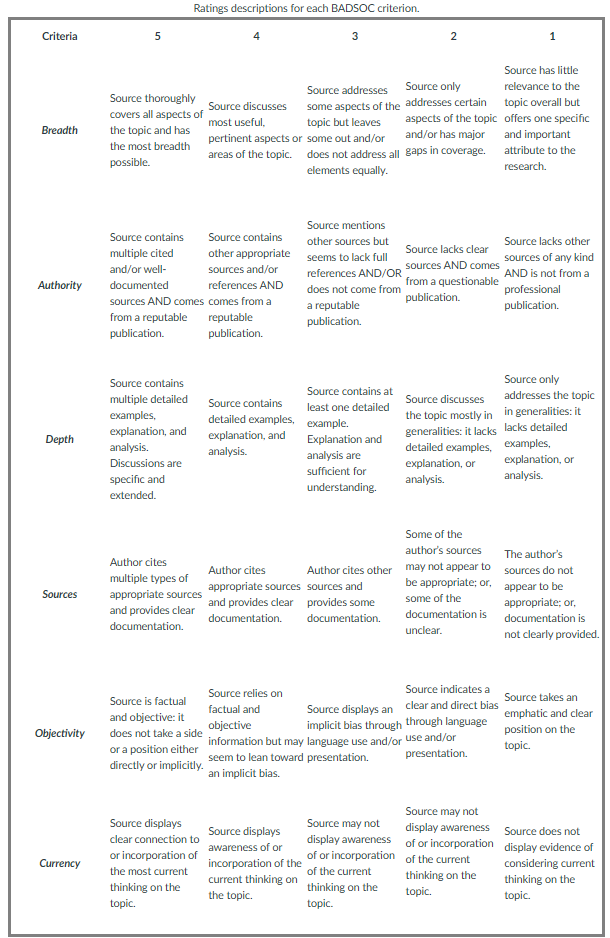

How does the research source fulfill the BADSOC criteria?

- How do the elements of the research source guide you through it and help you understand it?

After Reading a Research Source

- These are questions that you want to ask yourself after a section of reading and probably again after you finish the entire work (If it is a full-length text).

- Does this research source meet your needs better than others of its type?

- Does this research source have any particular features (tables, graphs, research approached, etc.) that other research materials for this assignment do not?

Reflection on and Connection with a Research Source

- Your answers to these questions will help you figure out how this research source fits into your topic and writing about that topic.

- How closely does this research source align with your research needs?

- How does this research source balance your research needs overall?

- Do you have other research sources that are similar?

- What unique insights does this research source provide?

Checking Sources for Bias-3

-

When you’re researching a topic, you often want “just the facts,” so that you can draw your own conclusions about what you’re reading. Scholarly articles are a good choice, since they are often written simply to report and discuss original research findings (you’ll learn about scholarly articles in this course). Or, web articles published by educational organizations, intended to teach or inform, can be helpful, too.

-

However, plenty of people (and organizations) publish with other intentions. They may want to advocate for a cause or a political issue. They may want to sell a product. It doesn’t necessarily mean that you can’t use their information. In fact, if you want to find opposing viewpoints or to gather examples of marketing or political strategies, etc., these kinds of publications might be just what you need. But, when you need unbiased information, they could lead you astray. You need to be able to spot bias.

Biased seeds

What are some signs that you’re looking at a biased or subjective source?

- If its purpose is to persuade, endorse, promote, market, sell or entertain. If you’re not sure, check the organization/publisher/magazine website for an “about” or “mission” link. If the site has motives beyond simply teaching or informing, then you need to be on guard for bias and inaccuracies in any information that you find there. If it presents a one-sided view of a controversial issue, or the author dwells on his or her opinion without giving equal time to opposing viewpoints. If it uses negative language to describe opposing viewpoints, products, candidates, etc.

How can you tell if a source is objective or unbiased?

- If it’s scholarly, it’s probably a safe bet. Objectivity is prized in scholarly literature…particularly in peer review. It remains neutral on controversial issues, giving equal time to each point of view. An unbiased author will try to fairly represent conflicting ideas, without trying to convince you that one is right.

- If its purpose is to teach or inform or disseminate research, it’s likely relatively safe from bias.

- On an organization’s website, look for an “about” or “mission” link.

- In an ebook, look for an introduction, or go to the publisher’s website.

- For an article, go to the journal, magazine or newspaper’s website and look for an “about” link

An Example of an Unbiased Source: Encyclopedias

- Encyclopedias and encyclopedia entries are great examples of unbiased, objective, factual information. Even though You’ll most likely need more than just encyclopedia entries for your research project, these reference materials are a course of information when you need to know more about a topic or subject.

** This information is adapted from the Richard G. Trefry Library’s Research FAQ’s page (apus.libanswers.com/faq/144927)

Research

Find and Evaluate the Source (News, Magazine, Reference Materials, Internet-Base Source)

- Review the BADSOC Research Source Review chart and notes

- Use the keywords you've developed and a search engine (such as Google) to search for sources (review our course page Using a Search Engine for some tips)

- Look at several sources that come up on your search. Try several of the keywords you've developed.

- Choose one of the sources that gives you some new information on your topic

- Read this source laterally to determine if the source of this information is reliable (see our course pages Online Verification Skills and Reading "Laterally" for instructions)

- Use the BADSOC Research Source Review chart and "Research Source Review Notes" questions to evaluate this source

- Consult our course page MLA Citation: Internet-Based Sources to develop an MLA Works Cited page citation for this source

Write Responses

- Your topic and keywords

- The MLA Works Cited page citation for the source you evaluated

- BADSOC ratings for this source (1-5 in each of the six criteria)

- Responses to the "Research Source Review Notes" questions (Summary, Your Research Goals, Virtues, & Limitations)

Summary

Write a 3-4 sentence summary of your source

Include a statement of the author’s overall argument (if there is one)

Your Research Goals

How does this source contribute to your research overall?

Virtues

What are the strengths of this particular source?

How do you envision using it to further your ideas along?

The source shows the related information about research topic, so I can expand my ideas about it.

What does the author do particularly well in this source?

The author can look at the result and immediately can find some ideas for the topic.

Limitations

What are the weaknesses of this piece of research?

The source is limited in specific subject, so we need to use different keywords to search more.

How will you account for this weakness in your research overall?

I think we may can look at the information from other sources to find more information for the researched topic.

Scholar Reading Journal Article

-

It can be a challenge to read a scholarly journal article. This page includes three videos that recommend specific methods and reading strategies to help you make the most of the time you spend deciding whether a particular article will help you with your research needs.

-

While videos #1 and #2 make similar recommendations, the visuals are very different. Watch both videos to see which one best communicates the information to your mind.

Video #1

- This first video (2:26) is from Pitt Community College Library. It discusses and points out the different sections of a scholarly journal article and recommends reading them in a certain order; watch the video for the demonstration and details. If you cannot see the video below, follow this link to the video on YouTube: How to Read a Scholarly ArticleLinks

1) Read the abstract 2) Read the Discussion / Conclusion 3) If the article is right for you. then continue to read the Introduction 4) Read the Methods 5) Read the Result 6) Read the References.

Video #2

-

This second video (2:34) is from Western University Library. It recommends the same method and reading order as the previous video, but includes cartoon drawings to illustrate the discussion.

-

In addition, this video recommends asking yourself the following questions while reading any scholarly journal article:

- What is the topic of this article?

- What do I already know about this topic?

- Do I agree with what this author is saying?

- Does this author agree with what others have said about the topic?

-

If you cannot see the video below, follow this link to the video on YouTube: How to Read a Scholarly ArticleLinks

Video #3

- In this Kishwaukee College Library video (5:10), librarian Tim Lockman goes step-by-step through his own process of reading a scholarly journal article. His conversational explanation of his reading process, alongside his visual examples, will be extremely helpful. If you cannot see the video below, follow this link to YouTube: How to Read a Scholarly Journal ArticleLinks

-

Use Modern Language Association (MLA)

-

Find & Evaluate a Scholarly Journal Article - In this research module, we’ve discussed what makes scholarly journals unique, how they contribute to your research process, how to read a scholarly article, and how to use EBSCOhost’s online database, Academic - Search Complete, to find scholarly articles. Now it’s time for you to do your own scholarly journal articles research and evaluate a source!

- Tasks (what you’ll do)

- Complete the following tasks:

- Review the BADSOC Research Source Review chart and notes

- Use the keywords you’ve developed to search EBSCOhost’s Academic Search Complete database for sources (review our course page Academic Search Complete: Scholarly Articles for instructions)

- Look at several sources that come up on your search. Try several of the keywords you’ve developed.

- Choose one of the sources that gives you some new information on your topic

- Use the BADSOC Research Source Review chart and “Research Source Review Notes” questions to evaluate this source

- Use the “Cite” feature to generate the MLA Works Cited page citation for your source [review our course page MLA Citation: Academic Search Complete (Scholarly Articles) for instructions]

- Written Response (what you’ll submit)

-

Include the following items to complete this assignment:

- Your topic and keywords

- The MLA Works Cited page citation for the source you evaluated

- BADSOC ratings for this source (1-5 in each of the six criteria)

- Responses to the “Research Source Review Notes” questions (Summary, Your Research Goals, Virtues, & Limitations)

Magazines versus Journals

- What’s the Difference?

- When conducting research, it is important to understand the differences between popular/general interest magazines, scholarly/professional journals, and industry/trade journals. If, after checking the descriptions below, you are still uncertain as to the category of the periodical you are using, ask your instructor or a librarian for help.

Popular/General Interest Magazines

-

The term magazine is usually applied to popular or consumer type publications that are generally for sale on newsstands.

- audience: presentation style is aimed at general public

- authorship: usually written by journalists or staff writers; the author’s name may or may not be noted

- documentation: there is usually no documentation of sources such as notes, footnotes, or bibliographies

- review process: articles printed in magazines are reviewed only by the editorial staff of the publication itself and not by any outside body

- appearance: magazines are usually printed on slick, glossy paper and contain both black & white and color pictures and photographs

- advertisements:numerous advertisements are included

- publishers: commercial publishers

- frequency: usually weekly, monthly, or bi-monthly

- examples: Time, Newsweek, Sports Illustrated, National Geographic

Scholarly/Peer Reviewed/Professional Journals

-

Scholarly journals publish original research in the sciences and social sciences, and essays, criticism, and reviews in the humanities. They are subject specific in focus, are written for the use of scholars, and are seldom sold by the issue on newsstands.

- audience: scholars, researchers, and students

- authorship: authors are experts or researchers in the specific field addressed; author names are noted, often with an indication as to their credentials

- documentation: articles contain extensive documentation including notes and bibliographies

- review process: articles are refereed or peer reviewed by an outside body of experts in the specific field covered

- appearance: scholarly journals are seldom printed on slick or glossy paper and are plain and conservative in appearance; they contain few, if any, pictures or photographs, though graphs and diagrams are used often

- advertisements: there is little or no advertising

- publishers: usually, though not always, published by professional organizations or academic institutions

- frequency: usually quarterly, semi-annually, or even annually

- examples: Journal of Applied Psychology, Political Science Quarterly, Modern Fiction Studies

Industry/Trade Journals

-

Industry or trade journals contain articles concerning a specific industry. These publications are usually sold only by subscription, though some can be found for sale on the newsstand.

- audience: intended to inform those involved in a specific industry or trade

- authorship: written by journalists, staff writers, or others in the field being addressed; the author’s name may or may not be noted

- documentation: generally no documentation of sources such as notes, footnotes, or bibliographies

- review process: articles are usually only reviewed in-house and not by any outside body

- appearance: trade magazines are usually printed on slick, glossy paper and contain both black & white and color pictures and photographs

- advertisements: numerous advertisements are included

- publishers: most are published by associations, though some are published by commercial publishers

- frequency: usually weekly, monthly, or bi-monthly

- examples: Advertising Age, Publishers’ Weekly, American Teacher, American Libraries

–> This information is derived from the Calhoun Community College Library webpages (lib.calhoun.edu/lib/periodical_types.html)

What Is Peer Review?

- Sometimes people refer to scholarly journal articles as peer-reviewed articles; this is because each article gets reviewed by other scholars who are the peers of the article’s author. To learn more about the scholarly peer review process, watch the following video from North Carolina State University (3:15). If you cannot see the video below, follow this link to YouTube: Peer Review in 3 MinutesLinks

Scholarly versus Popular Sources

- If magazine articles and scholarly journal articles can both make good research sources, what are the real differences between these two types of periodicals? For further explanation, watch the following video from Carnegie Vincent Library (4:11) for a good comparison of scholarly and popular sources. If you cannot see the video below, follow this link to YouTube: Scholarly and Popular SourcesLinks.

Scholarship as Conversation

-

Even though you might read a scholarly journal article all by yourself, it’s important to realize that the article you’re reading allows you to enter a conversation about the subject. Writing scholarly journal articles allows professors and researchers to share, propose, and critique ongoing work in their field.

-

For example, scholars have been writing about Shakespeare for centuries; each new scholarly journal article on Shakespeare adds to and carries forward the centuries-long conversation about Shakepeare’s work. When you read one of these articles, you are entering the conversation yourself.

-

The following video from West Virginia University Libraries (3:02) explains this concept in more detail. If you cannot see the video below, follow this link to YouTube: Scholarship as Conversation